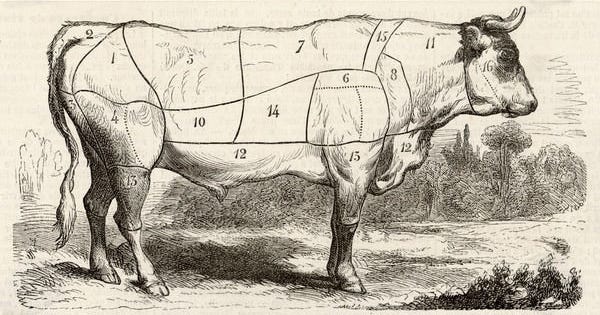

Trepa and Galton's dressed ox

Why Trepa wants to be a prediction platform that rewards numerical accuracy.

This is a post by cofounder Jong (https://x.com/guyukyukgu).

The original accuracy game: Galton and the fat ox

It is the year 1906, and Plymouth is hosting the West of England Fat Stock and Poultry Exhibition. Sir Francis Galton, half-cousin to Charles Darwin, wanders through the fair and stumbles upon a weight-judging competition with roughly 800 participants. The rules are simple: whoever guesses the weight of a fat (I’m just citing Galton lol), dressed ox would win prizes. A “dressed ox” means the animal has been slaughtered, cleaned, and prepared for butchering.

After the event, Galton borrows the tickets containing all estimates to crunch some statistics. After removing 13 faulty entries, he keeps 878 valid submissions. Surprisingly, the median estimate (which he called the vox populi) is 1,207 pounds while the actual weight is 1,198 pounds: an error of only 0.8%.

However, a later 1907 enquiry will reveal that the actual average estimate was 1,197 pounds, lowering the error to less than 0.1%. And much later, archival work in 2014 will show that the true weight wasn’t 1,198 but 1,197 pounds. Meaning: the average guess perfectly predicted the ox’s weight.

This anecdote became the classic demonstration of the “wisdom of crowds,” first conceptualized in Nature under the term democratic judgement.

What this has to do with Trepa

I’m telling you all this because the parallels to Trepa are surprisingly direct. At its core, Trepa shares the same competitive spirit and incentives as the ox weight-judging contest, only applied to any numerical outcome instead of an ox’s weight.

Is the weight of an ox inherently interesting? Probably not. But once you frame it as a prediction competition with monetary incentives, suddenly hundreds of people engaged. The organizers tapped into one of the strongest drivers of human behavior: speculation as motivation. As Galton put it, the “sixpenny fee deterred practical joking, and the hope of a prize and the joy of competition prompted each competitor to do his best.”

Trepa is no different really. The whole concept is fairly straightforward but the fact that nearly 800 people voluntarily participated in 1906 shows how powerful a simple competition framework can be.

(Btw, Sir Francis Galton would have made an excellent Trepa mascot if it weren’t for, you know… the eugenics stuff 🤷.)

Humans honor precision

Even more than a century later, people remain obsessed with figuring out how close they were. The appeal of measurable accuracy shows up everywhere, from GeoGuessr, a simple location-guessing game that somehow evolved into a viral multi-million-user platform, to the bizarrely captivating German pretzel-cutting contest, where participants try to slice a pretzel into two perfectly weighted halves, to long-running shows like The Price Is Right, which has sustained decades of popularity by asking contestants to estimate retail prices as precisely as possible. Precision is both fun and status-bearing.

In sports betting, a Huddle analysis shows that numerical player props (yards, touchdowns, etc.) are now the fastest-growing portion of NFL betting. On Polymarket and Kalshi, many of the highest-volume markets are also numerical: prices, yields, GDP prints, NFP numbers, election margins, weather data.

More recently, Brian Armstrong, CEO of Coinbase, praised participants in an internal earnings prediction challenge, noting that ten users landed within 1% of actual results and one was off by only 0.06%. Precision demonstrates competence.

All of this suggests a large and enduring latent demand for speculative competitions based on numerical accuracy.

What Trepa is, fundamentally

There are many ways I could define Trepa. I could do it positively, by listing what Trepa is, or negatively, by listing what it is not. But the quickest path to the core is the comparative method: looking at Trepa alongside a familiar reference point such as a binary prediction market (e.g. Polymarket).

Both prediction markets and Trepa ultimately care about accuracy, but they measure it differently. Prediction markets evaluate the collective accuracy of the crowd, usually through metrics such as the Brier score. Trepa puts measuring and rewarding individual accuracy first, while still aiming to achieve platform-level accuracy that rivals or even surpasses prediction markets for numerical outcomes.

In that sense, the relationship between prediction markets and Trepa’s accuracy-based, pari-mutuel, precision-prediction model is likely more complementary than adversarial. Prediction markets expect users to trade probabilities to surface private information as a platform-wide signal while Trepa expects users to deliver a point estimate, which can then be aggregated into a summary statistic like the average or the median or more sophisticated versions thereof. Each format captures a different aspect of how humans forecast. Together they form a richer ecosystem for understanding the future.

TL;DR: Trepa is, at its heart, a competition in the same spirit as the 1906 Plymouth ox-weight contest. It is fundamentally about individual accuracy. By encouraging each participant to give their best possible numerical estimate, Trepa produces an aggregate signal that benefits from the wisdom of crowds. The resulting “best guess forecast” should, over time, track the true outcome remarkably well.

What’s next

Catch the Trepa team IRL at Solana Breakpoint from the 8th to the 14th of December. I’ll be pitching at the Superteam Demo Day on the 13th.

Keep an eye on our X account for the mainnet launch date announcement.

We’ll also release our DOCS soon, including some of the exact math behind our convex, accuracy-score and time-weighted pari-mutuel funding mechanism (yes, it’s a mouthful).

Thanks for reading this far. See you in the trenches. LFG.

P.S. I just found out that an ox is a castrated bull trained for work. RIP Galton’s ox.